Going into Goodman Gallery, one has to first move through the city. Johannesburg is a place that brims with energy: dense, heterogeneous, and restless with difference. It is a city of collisions and vibrancy, a place where nothing feels still. And then you arrive at Goodman. The gallery sits almost as an island, its white modernist form radiating a kind of calm against the turbulence of the streets around it. Entering that space feels like crossing a threshold, moving into another world altogether. It is precisely this transition — from the rush of Johannesburg into the quiet clarity of Goodman — that sets the stage for an exhibition of this nature.

In the lobby-like space at the entrance to the exhibition, I encountered works by Maxwell Alexandre, Pélagie Gbaguidi, and Ibrahim Mahama. The pieces positioned there — more modest in scale yet no less commanding — hung side by side as a kind of portal into the rest of the show. Together, they set the tone for Carriers and introduced the contrasts that would reverberate throughout. The exhibition title speaks directly to acts of carrying, and indeed, across the rooms one finds bodies carrying literal burdens: young men and women hauling global capitalist brands in Alexandre’s works, or Mahama’s figures dragging fragments of locomotives. Yet what struck me most in that initial encounter was not the theme of carrying itself, but the conversation that opened up between these three artists. The immediacy of the encounter was undeniable. Even before I understood the curatorial logic of the exhibition, what confronted me was difference: difference in medium, difference in style, difference in articulation. Each artist spoke in their own language, and the contrasts were as palpable as the walls they were hung on. And then, reading further, I realized that all three were grappling with the project of decolonization.

And so it struck me, standing there in the gallery, that perhaps what I was witnessing was not only an exhibition, but a moment. In the weeks leading up to my visit, there had been heated conversations around articles written about galleries, art fairs, and the broader art world in South Africa. What was interesting to me about that discourse was not only the criticisms themselves, but the sheer plurality of them. There were tensions, divergences, and sometimes outright contradictions. Yet rather than seeing this as a problem, I read it as a sign of maturity. When long-standing institutions begin to face voices that are sharp, varied, and unafraid, something important is happening. These are not just murmurs of discontent; they are signs that the intellectual and creative community — particularly black and brown South Africans — are entering a new phase, one in which there is no longer a single “correct” voice. Johannesburg, with its dynamism and heterogeneity, seems like the natural ground for such a shift. It is a city that generates plurality.

And that is precisely what I felt walking into Carriers. The exhibition was not presenting decolonization as a unified theme or slogan. Instead, what emerged was decolonizations — in the plural. This plurality resonates with the intellectual turn toward the “pluriverse,” the recognition that there are many worlds, many voices, many realities. To speak of decolonizations in the plural is to acknowledge that there is no singular path, no homogeneous experience of being colonized, nor a single way to resist or reimagine. Historically, strategic essentialisms were necessary. Gayatri Spivak used the phrase to describe how marginalized groups could temporarily adopt a simplified, shared identity in order to mobilize against oppression. One can think also of the Negritude movement, or similar currents in Latin America, where identity was essentialized in order to forge collective strength. In those times, essentialism was a tool for liberation. But what I sensed at Goodman was that we are living in a different moment.

Now, within the very communities born from those earlier liberatory movements, nuance is proliferating. Views diverge, sometimes starkly. Blackness itself appears in multiple registers — shaped by class, geography, history, and aesthetics. This is not weakness, but strength. It signals the freedom to differ. And what was staged in Goodman Gallery was precisely this: decolonization refracted into multiple forms, multiple voices, multiple strategies. The white cube, for all its contradictions, became a stage on which difference did not collapse into sameness, but was allowed to speak in its fullness.

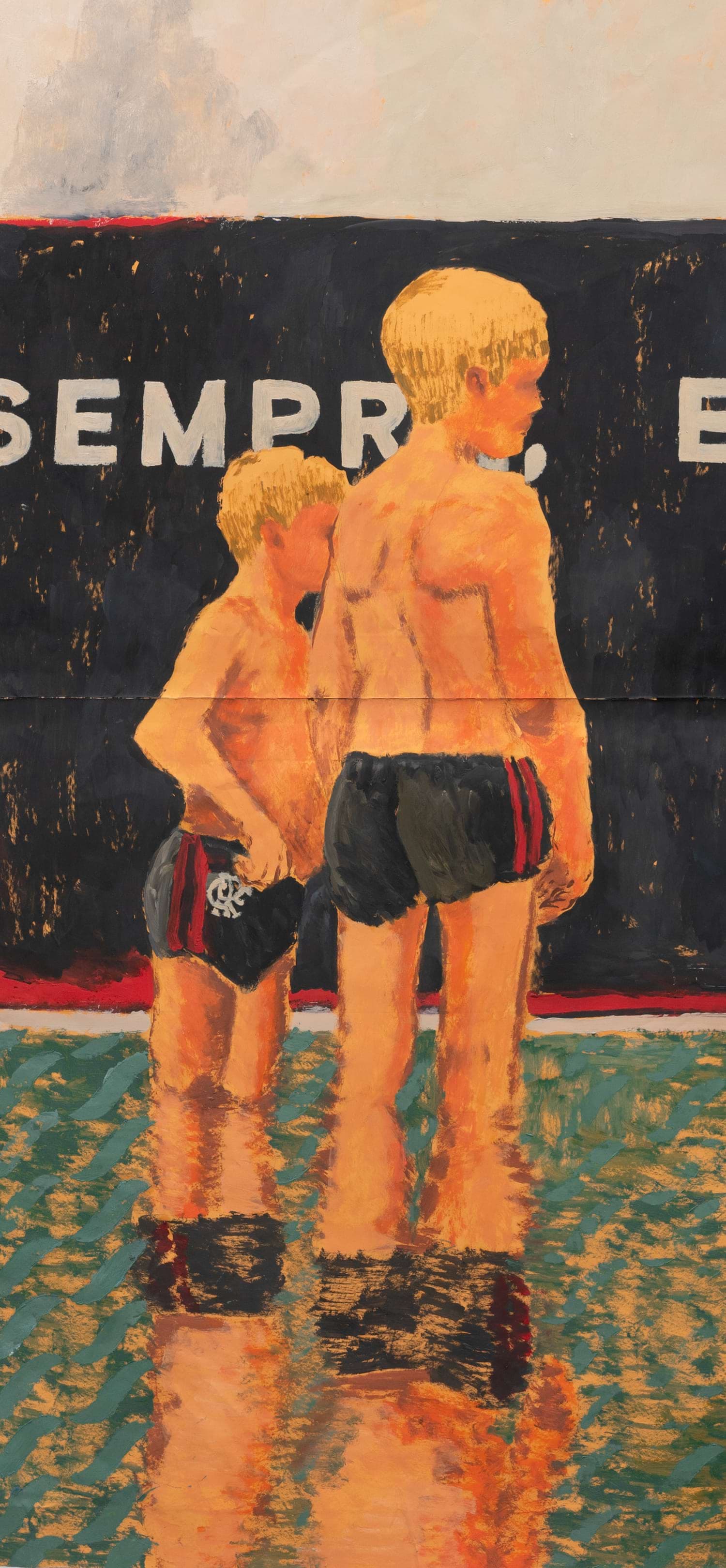

When I think back to the three artists, what strikes me most is the distinct way each of them stages the question of colonization and its afterlives. With Maxwell Alexandre, the initial impression is almost seductive. His paintings of children swimming or riding bicycles to deliver goods carry a romantic surface. The brushwork and the scenes draw us in with lightness, even innocence. And yet, as the narrative begins to unfold, the works take on a darker weight. The pool, that symbol of leisure and freedom, reveals itself as a site of exclusion, accessible only to some and barred to others. The young delivery riders, at first playful in appearance, are in fact caught within the global circuits of exploitation — Uber and other capitalist brands that shape contemporary life in Brazil and far beyond. Alexandre’s genius is to show how neocolonial power operates under the guise of everyday normality, almost invisible in its pervasiveness. What begins as charming quickly turns sinister; what looks romantic becomes nihilistic. In his works, the forces of global capital seem overwhelming, their opacity terrifying once recognized.

Ibrahim Mahama’s works, by contrast, open onto a different register. They summon the bureaucratic and infrastructural dimensions of a kind of “classical” colonialism. Mahama draws from the material residues of Ghana’s railway system — locomotives, paperwork, ledgers — technologies that were never neutral, but strategic tools for extracting value. Rail, after all, is the technology of moving goods efficiently, and thus of embedding racial capitalism into the fabric of everyday life. Encountering Mahama’s collaged surfaces, one immediately senses the presence of black bodies laboring on the railways, conscripted into the colonial economy. Yet unlike Alexandre’s scenes, which end in a kind of hopeless recognition, Mahama’s practice brings new life to these remnants. The men who work with him today, salvaging disused train parts, are not trapped in exploitation but participating in the re-making of meaning. Mahama mimics the aesthetic logic of colonial bureaucracy — the stamps, the stains, the systematic recording of lives and labor — but he reorients it. In his hands, the archive becomes not only a record of subjugation but also a material for transformation.

Then there is Pélagie Gbaguidi, whose works register as starkly different again. Where Alexandre entices with surface and Mahama excavates infrastructures, Gbaguidi works in immediacy. Her paintings are not representational in the conventional sense; they are expressions, phenomenological encounters with body, material, and trace. One feels the presence, the pigments, the gestures of her arm. To stand before her canvases is to feel ritual. They evoke the atmosphere of a sacred site, where candle wax, blood, and layers of scarred surfaces bear witness to acts that have taken place. In her case, the body is both medium and archive: scarification, pain, blood, and memory are inscribed into the work. The result is not nihilism in a psychological sense, as with Alexandre, but torment that is embodied and visceral. It is ritualized memory, expressed not through representation but through the trace of bodily action.

Taken together, these three artists do not echo one another. They diverge, profoundly. And yet their divergences are what make the exhibition so powerful. Each articulates colonization and decolonization in a different modality — Alexandre through the sinister banality of neocolonial brands, Mahama through the infrastructures of industrial extraction, Gbaguidi through the immediacy of ritual scars. They circle common themes, but each insists on a different articulation. It is precisely in this heterogeneity that the exhibition finds its strength: one history, refracted into multiple expressions, refusing to collapse into a single voice.

My take on this work being situated in Johannesburg today, and at the Goodman Gallery specifically, is crucial. When Gayatri Spivak spoke of strategic essentialism, or when we think of the Negritude movement, the logic was clear: essentialism could be deployed tactically, as a means of uniting a people in order to break free from domination. Yet as Jean-Paul Sartre argued to Léopold Senghor and Aimé Césaire — a moment recorded by Frantz Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks, in his chapter on the lived experience of the black man — such movements were destined to die. Their task was to construct an essence only so that essence could ultimately be dismantled. Essentialism was a bridge, not a destination. Freedom would be marked not by unity, but by multiplicity.

Seen in this light, Carriers feels apt. Imagine the three artists — Maxwell Alexandre, Ibrahim Mahama, and Pélagie Gbaguidi — not merely coexisting in the space of the Goodman Gallery, but engaged in debate with one another. Each would argue for their approach, their method, their articulation of colonization and its afterlives. That conversation would not signal fragmentation, but maturity. It would reveal the stage I argue we are in now: one where no single voice or institution dominates, where plurality is not a threat but a sign of life. This matters especially in a time when “blackwashing” has become fashionable — when black artists are sometimes invited into institutions primarily to perform a generic blackness, to fill a role rather than to speak in their own voice. Against that backdrop, the multiplicities staged in Goodman begin to push back against flattening. They refuse the homogeneity that was once both imposed by colonialism and mobilized in liberation. Here, difference is not assimilated but affirmed.

Whether by intention or not, the exhibition has become a stage for multiplicity at precisely the right moment. In Johannesburg, in South Africa, in a global cultural climate marked by both algorithm driven homogenisation and resurgent debates about the role of institutions, Carriers gives form to the idea that decolonization is not about sameness but divergence. In that divergence lies a deeper humanism: one that resists clustering people into neat categories, one that allows subjectivity to stand on its own terms. This, after all, is what Fanon himself enacted when he broke with the positions of Senghor and Césaire, insisting on his own trajectory. To stand in Goodman Gallery today, in the presence of Alexandre, Mahama, and Gbaguidi, is to encounter that same possibility. Not a single voice, but a chorus of dissonances. Not a uniform blackness, but blacknesses. Not one decolonization, but decolonizations. That, I would argue, is the deeper achievement of Carriers: to remind us that true decolonization is the freedom to differ — so let the arguments come, let the disagreements grow, for they are the signs of a new maturity.