Once seen as a creative backwater thanks to its association with craft and domestic labour, textile or fibre art has emerged as the medium of our moment. The octogenarian Sheila Hicks’s vast, amorphous, rainbow-hued experiments with fibre filled Paris’s Pompidou Centre in 2018, while the late Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz’s huge, witchy, labial rope sculptures haunted London’s Tate Modern in 2022.

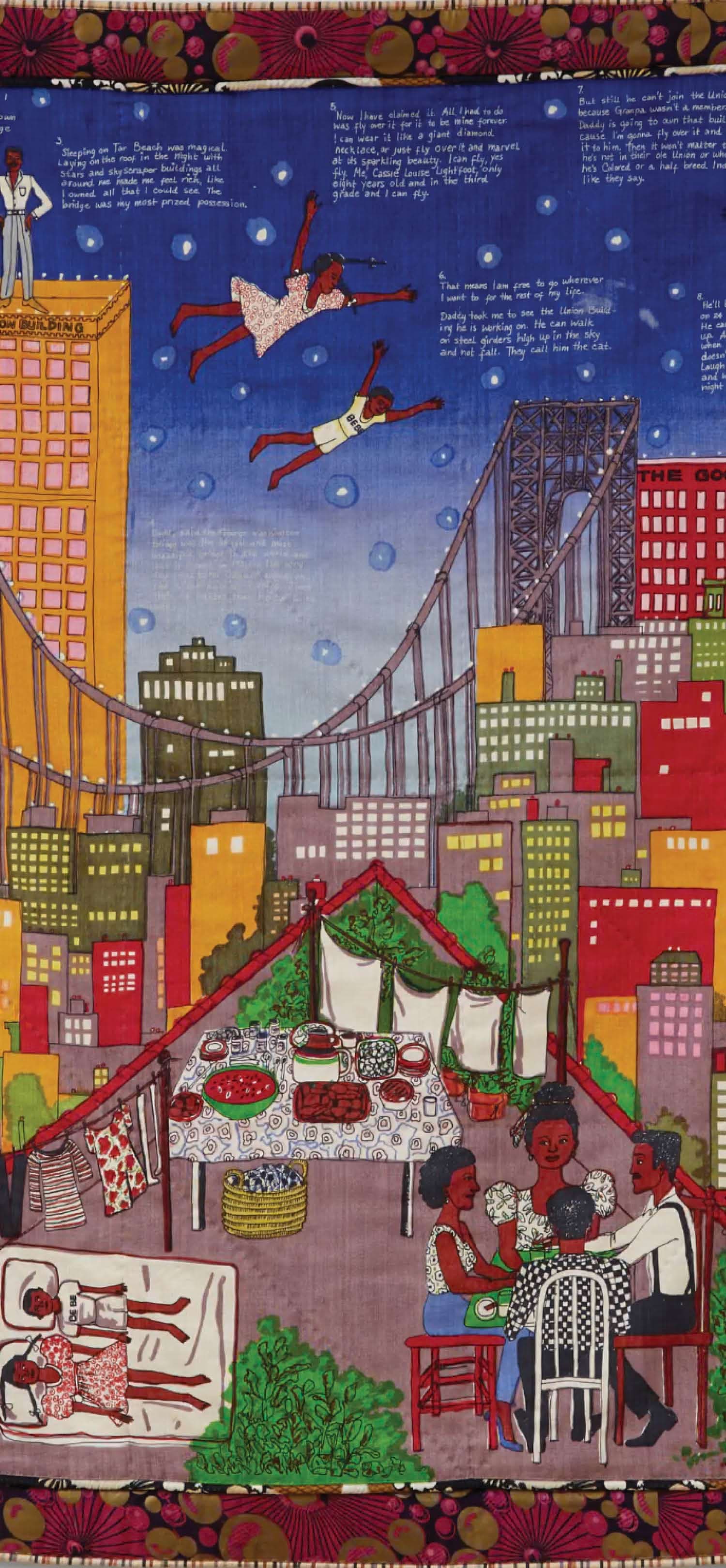

Now these leading lights can be found within Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art. A survey exploring the movement’s inter-generational cross-currents, it encompasses everything from hand-embroidered hankies to big sculptural installations. “Textiles as a term is so capacious and expansive,” says Lotte Johnson, one of Unravel’s three curators. “We’re looking at how cultural dialogues as well as poetic and personal associations speak across geographies and time.”

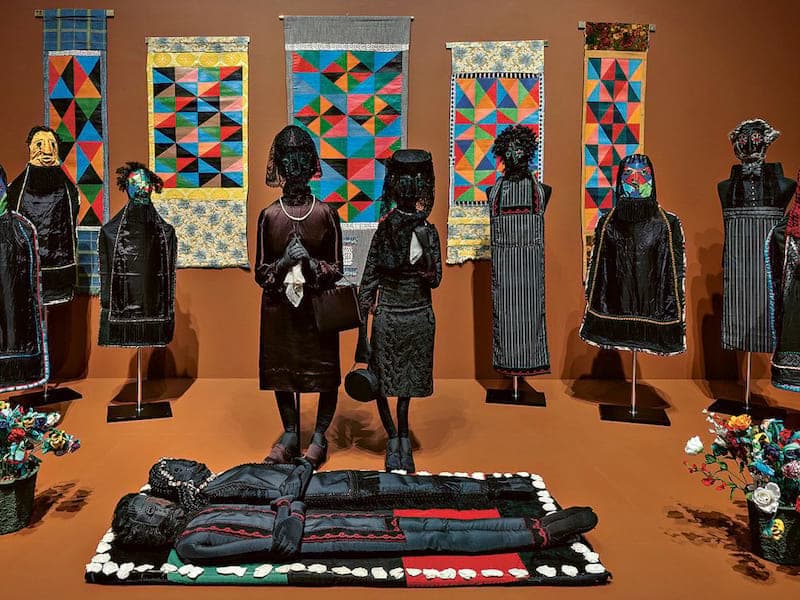

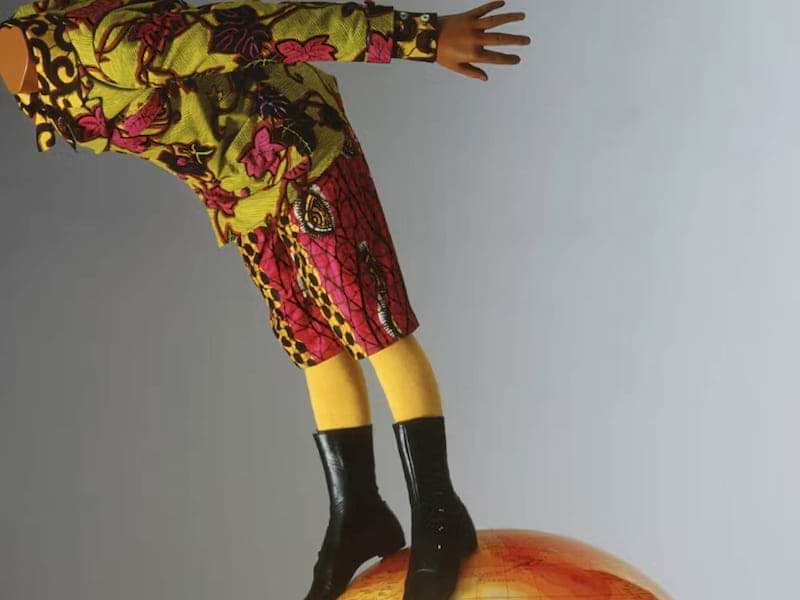

The thread through the exhibition’s strikingly varied creations is textiles’ potential for political expression. Fibre art first emerged in the 1960s, notably through feminist artists reclaiming “women’s work” for subversive ends. One of the most celebrated artists to come of age then, Judy Chicago, collaborated with needleworkers to create her 1980s series depicting the intensely physical experience of giving birth. This foreshadows more recent explorations of identity and the body, such as the South African artist Nicholas Hlobo’s libidinal anthropomorphic creations on canvas with leather and ribbon. “He uses ribbons because of their association with women’s garments and thus rebellious possibilities,” says Johnson. “These works have been key for his own exploration of sexuality as a gay man.”